When Marine Science Doesn’t Reach Shore: Why Better Communication Can Help Save the Ocean

Últimas noticias

A pioneering genetic catalogue reveals hidden biodiversity in Basque estuary sediments

Uhinak Technical Committee Sets the Key Points for the 7th International Congress on Climate Change and the Coast

“We fishermen are the ones who earn the least”

ÁNGEL BORJA, researcher in Marine and Coastal Environmental Management

For more than forty years, I have devoted my life to studying the sea. I’ve worked on projects about pollution, biodiversity, and climate change, and I’ve always been fascinated by its complexity. But over time, I’ve learned something as valuable as any data or model I’ve ever used: knowing the ocean is of little use if that knowledge doesn’t reach those who make the decisions to protect it. In other words, communicating science better is essential.

That reflection is the starting point of the work we recently published in Frontiers in Communication, together with colleagues from various European countries. The article grew out of a summer course organized by AZTI in San Sebastián in June 2024, in collaboration with six European projects. In it, we explore how to improve communication between marine science, policy, and society — and why doing so is vital to protect the ocean and address challenges like climate change and biodiversity loss.

Índice de contenidos

When Science Doesn’t Reach Shore

Within the scientific community, we know a lot about the sea. We understand how currents shift, how nutrients are distributed, what effects warming and pollution have on ecosystems, and how different components of those ecosystems interact. But between scientific knowledge and real action — a law, a management measure, or a change in social behavior — there’s a gap.

That gap has much to do with how we communicate science. Scientists speak a technical language, full of numbers, models, and acronyms. Policymakers and managers, however, need clear, applicable messages that fit within their timeframes. And society — which ultimately feels the consequences of those decisions — needs to understand why these issues matter in daily life and how they affect them personally.

If each group speaks its own language, the information gets lost along the way. No matter how rigorous marine science is, it has little impact if it’s not understood or used.

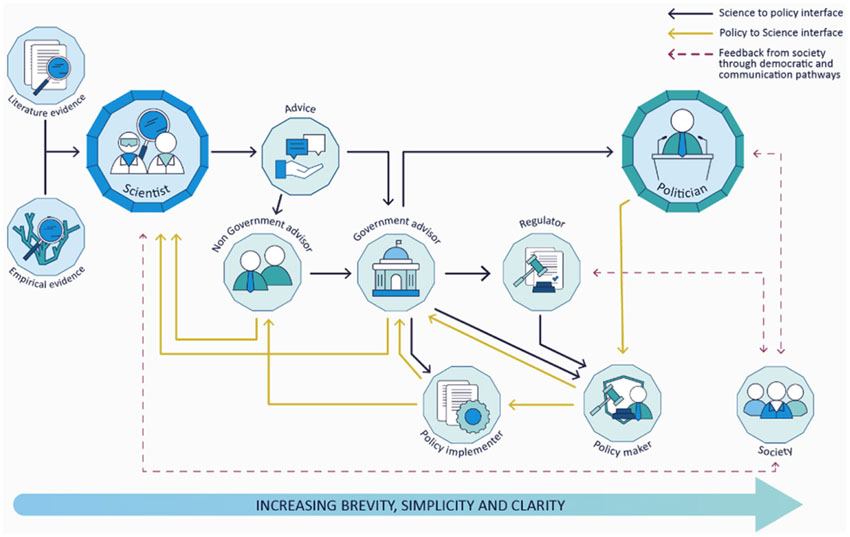

A Two-Way Dialogue

In our article, we propose a new model of two-way communication. Traditionally, scientists produce knowledge, publish it, and wait for someone to use it. But that rarely happens. We believe communication should begin at the start of the scientific process, not at the end.

This means involving managers, policymakers, and citizens from the early stages of research — defining together which questions are most relevant. If a study is designed from the outset with end users in mind, the chances that its results will translate into real decisions grow enormously, because the questions are framed to seek solutions.

Moreover, communication shouldn’t be a one-off act (like a press release or a talk) but an ongoing process of exchange and trust. Scientists also need to listen — to understand the needs, conflicts, and priorities of those who make decisions.

Figure 1. The interfaces between science and policy — and vice versa — should foster complementary collaboration among all stakeholders, actively involving society as a whole.

Training Scientists to Communicate

Communicating science isn’t intuitive. It requires training and practice. Just as we learn to handle instruments or analyze data, we should also learn to explain what we do clearly, rigorously, and empathetically — while appealing to the emotions of those who will use our information or benefit from our work.

That’s why we propose that communication should be part of scientific training, and that research projects should dedicate time and resources specifically to knowledge transfer. Communicating well is not a secondary task; it’s part of scientific responsibility.

Likewise, policymakers and institutions also need training to interpret scientific information wisely. Only if both worlds understand each other can we make better decisions about the ocean.

Examples That Work

Across Europe, there are already initiatives showing that this shift is possible: dialogue platforms between scientists and managers, educational programs, and summer schools where young researchers learn to express themselves in a clearer and more visual way.

In the Basque Country, AZTI has promoted similar initiatives with great success — for example, through the Escuelas Azules (“Blue Schools”) program, where we use tools like comics to engage young people in an interactive way.

These experiences show that investing in communication multiplies science’s impact. A technical report that influences a management decision, or an article that inspires someone to change their behavior, are powerful examples of knowledge turning into action.

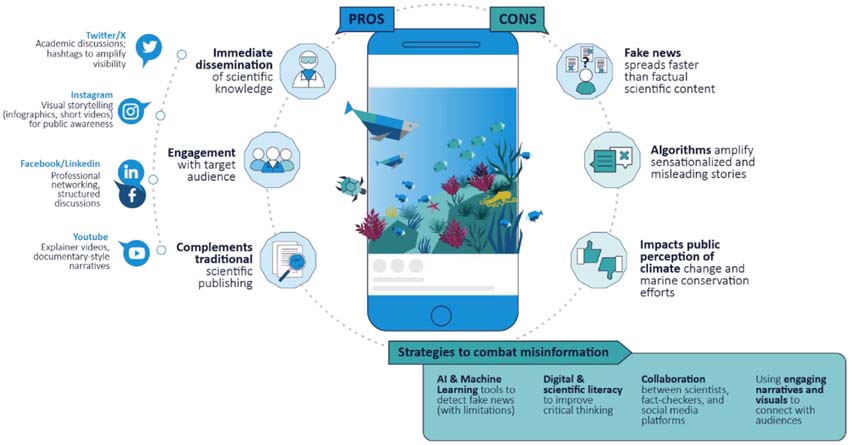

Figure 2. The role of social media in spreading scientific knowledge and the associated challenges.

An Urgent Task

Our work is framed within the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030), whose goal is precisely to bring science closer to action. In this context, improving communication is not a luxury — it’s a necessity.

The ocean faces growing pressures: biodiversity loss, pollution, overfishing, warming, acidification. We need policies based on solid scientific evidence, but we also need an informed society that understands that protecting the sea means protecting ourselves and our health.

Marine science cannot remain confined to laboratories or academic papers. It must reach offices, classrooms, and social media. Only then can we ensure that knowledge turns into real, informed decisions — decisions that help preserve the ocean for generations to come.