Flying Trawl Doors: Technology for More Sustainable Fishing

Últimas noticias

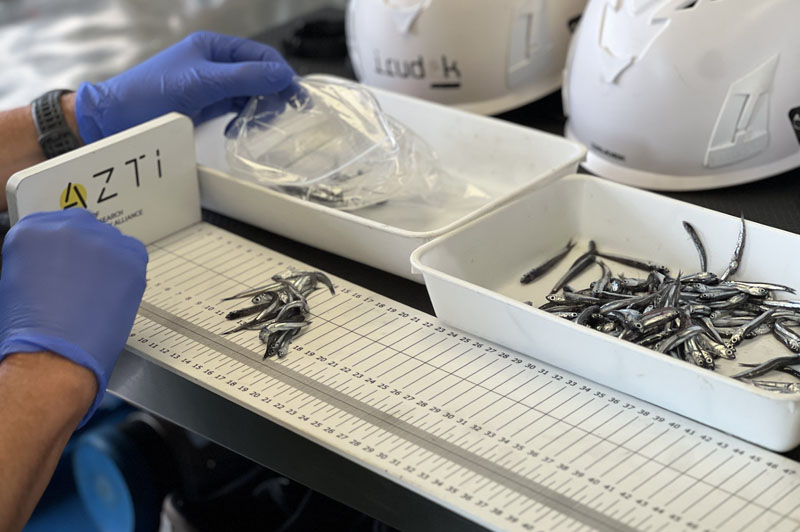

AZTI wins the 24th JACUMAR Award with a pioneering PCR method to determine the sex of sturgeons

JUVENA 2025: The abundance of juvenile anchovies in the Bay of Biscay has doubled the historical average

Ethics in Artificial Intelligence for Food and Health: From “Can Do” To “Should Do”

MIKEL BASTERRETXEA, expert at Technologies for ustainable Fisheries

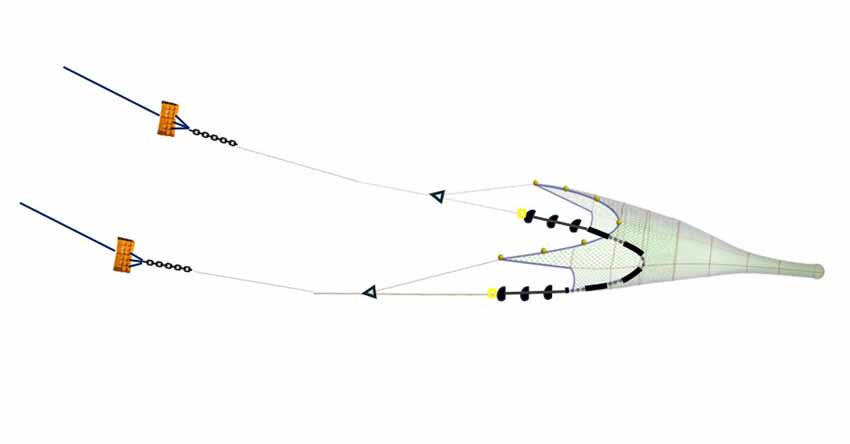

In bottom trawling, every part of the fishing gear affects both how effective it is and how much impact it has on the environment. One key element is the trawl doors. These devices, which keep the net open horizontally, have traditionally been dragged directly along the seabed—causing visible damage to sediment habitats. The grooves they leave behind not only alter the seafloor structure but also add to the pressure on fragile bottom ecosystems.

A new technological alternative, however, is gaining ground in the fishing sector: semi-pelagic trawl doors, more commonly known as flying doors. Unlike traditional ones, these doors can be adjusted to control their height above the seabed. This means they can “fly” while moving forward, keeping some distance from the bottom and reducing—or even eliminating—direct contact with it.

This is no small change. Flying doors not only reduce environmental impact, they also bring clear operational advantages. Because they generate less hydrodynamic drag, they allow vessels to use less fuel while maintaining the same fishing conditions. Several studies (including Franco et al., 2013; Grimaldo et al., 2015; and Eayrs et al., 2012) confirm these reductions, although results can vary depending on the vessel.

To work properly, flying doors rely heavily on good sensors that monitor their position and behavior in real time. Knowing exactly how high they are above the bottom is essential so that adjustments—like vessel speed or cable length—can be made from the bridge to ensure safe and efficient performance.

Technology centers like AZTI are testing and developing these doors in different projects to measure precisely how much they reduce environmental impact and energy use. Their results are helping build a stronger case for large-scale adoption. In this context, between June 1 and 15, Spain’s Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food carried out trials to compare the impact and fuel savings of flying doors versus traditional bottom doors. These tests took place during the ministry’s annual survey on improving trawl selectivity in the Bay of Biscay, under the scientific direction of the AZTI Foundation and aboard the research vessel Emma Bardán.

Still, there are hurdles to widespread adoption. The cost of the sensors and control systems can be a barrier for some vessel owners. Operating them also requires changes in traditional trawling maneuvers—something that, in a sector as experienced yet conservative as this one, takes time. And there’s another practical issue: since flying doors don’t touch the seabed, they don’t create the “sediment curtain” that in some areas helps gather fish, which may in certain cases affect catches.

Even with these limitations, flying doors are a significant step toward more responsible trawling, in line with the growing demand for sustainability in fisheries management. This is not just a passing trend, but a technology that—if implemented well—can strike a balance between productivity and conservation. And in an ocean with a future, that balance is more necessary than ever.

If you’d like to explore other technologies for more sustainable fishing, you can download our full report on the subject.

This article was originally published in the magazine Ruta Pesquera.