Content index

Most nowadays existing animal groups originated in the sea after the Cambrian explosion, 540 million years ago, before there was life on land. In that time, the great diversity of life in the sea sheltered trilobites, stem-group arthropods such as the large predator Anomalocaris, crustaceans, sponges, early chordates, worms, and squid-like creatures. The beginning of extensive land colonization by plants was millions of years later, during the Devonian (~390 Ma), which was facilitated through interactions with symbiotic fungi. Long after this transition, the coevolution between flowering plants with insects spurred the vast diversification of both groups.

Is the dominance of terrestrial diversity an historical phenomenon or does it rather obey to general ecological theories? Is the Ocean a “deathtrap” favouring species extinction as suggested by Miller and Wiens in 2017? One of the well-known rules in ecology establishes that the number of species found in an area increases with the size of the area. As oceans cover 71% of the Earth’s surface and have harboured life for much longer than land, one would expect that oceans hold a greater number of extant species than land. However, less than 15% of multicellular eukaryotic species currently described are marine, 80% live on land and 5% in freshwater. This diversity conundrum was pointed out by Robert May in 1994.

Although widely recognized, explanations for the diversity conundrum have often been limited to particular species groups or focused on testing specific hypotheses, such as how specific terrestrial environments permitted high speciation. In our paper published in Oikosi, we get deeper into the diversity conundrum by focusing on the limitations of marine pelagic diversity compared to land and freshwater diversity.

There are 2.16 million described species in our planet. One challenge underpinning different biodiversity patterns across land and ocean is that undescribed and cryptic species may be more abundant in marine environments. The difficulty of exploring remote and deep seas, and the estimated high number of species still undescribed could alter the estimated number of species in each realm. There are currently ca. 247,447 known valid marine species living in the oceans, which continue to be discovered steadily at a current average of 2,332 new species per year, i.e. 0.95% over the total marine species richness. The rate of terrestrial species description is about 16,000 species per year, i.e. 1.02% over the total terrestrial species richness, a percentage similar to that of marine species. Therefore, it is very unlikely that sampling bias would be the sole explanation for the observed imbalance of life diversity comparing oceanic and terrestrial biomes.

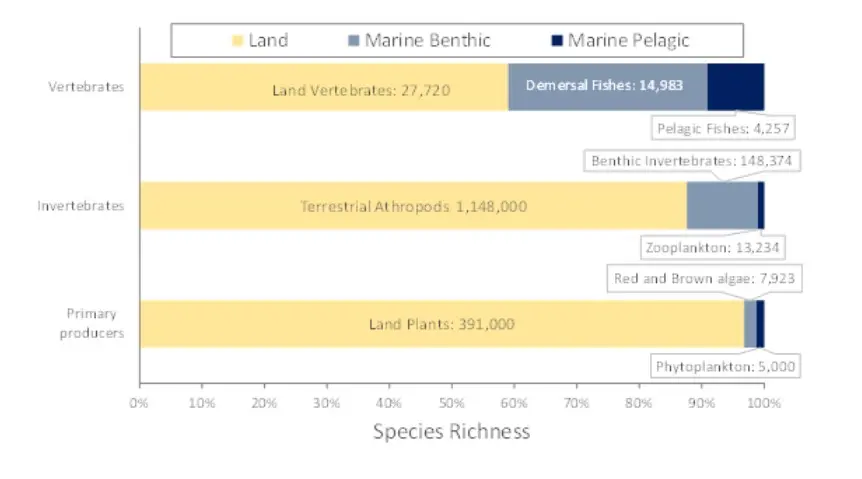

We reviewed the total species richness across taxa, trophic groups, and realms, according to the existing literature and a compilation of global data, shown in Fig. 1. Within low trophic levels, we found significant differences in diversity patterns between marine and land realms, particularly when comparing sunlit benthic and pelagic domains (Fig. 1). The species richness of primary producers in land and freshwater environments (391,000 species of vascular plants) is two orders of magnitude higher than that of marine eukaryotic phytoplankton (5,000 species). Diatoms are typically a dominant group in the pelagic domain, however, there are significantly more species in the benthic (8,770) relative to the pelagic domain (1,800). Arthropods diversified both in marine and land domains, and the described number of marine species is also substantially smaller than that of land species (Fig. 1). Concerning vertebrates, similar number of species has been described for fishes, as for terrestrial representatives (mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians combined). However, marine fishes are only half of the total fish diversity.

In summary, significant differences in species richness between marine and land realms are found particularly in primary producers and invertebrates, and mainly when comparing sunlit benthic from pelagic domains. The physical structure of the environment is therefore at the basis for understanding the disparity in diversity patterns.

At the global scale, the continental shelves include the areas with the highest regional species richness, such as the tropical coral reefs, in contrast to the pelagic domain.

Fig. 1 Relative species richness according to the habitat domain (marine pelagic, benthic and terrestrial) and biological group.

The Ocean is in continuous motion, and so all seas are potentially physically connected, regardless of strong differences in oceanographic and chemical properties that generate biogeographic pelagic provinces. One of the key differences is the capacity of some organisms to attach to or live in close association with soil or the seafloor and maintain position, in contrast to the pelagic domain. The marine pelagic domain is a fluid environment characterized by near continuum horizontal and vertical axes where planktonic organisms drift passively by four main mechanisms: Brownian diffusion, sedimentation (i.e., sinking), convection, and advection. The sinking velocity of particles through the water column increases with the weight of the particle according to the Stokes’ law, hence shaping the body size of planktonic organisms (i.e., larger plankton cells tend to sink faster than smaller ones). This process, termed the Stokes’ law, mainly determines the small size of phytoplankton. In the open ocean, photosynthetic organisms must either afloat or be small enough that their sinking rates are slow and they stay in the light.

In addition to sinking, advection process is also suggested to be important in terms of body size in plankton. A recent study by Villarino et al. (2018) in Nature Communications on plankton β-diversity revealed a negative significant relationship between body size and dispersal scales for taxa ranging from bacteria to small fishes. This suggests that less abundant large-bodied communities have significantly shorter dispersal scales than more abundant small-bodied plankton. Larger planktonic organisms with longer generation times and smaller population densities might be more sensitive to stochastic local extinctions, loss of gene flow, and ecological drift. Consequently, we suggest that body size for passively dispersing organisms with sexual reproduction in open ocean is constrained not only by the abovementioned sinking process, but also by ocean advection, via the logarithmic decline between the geographic range of a species and its body size. We tested this hypothesis by relating the body size of 368 phytoplankton species and 412 zooplankton marine species with an estimate of species geographic range. The log-log relations are weak but significantly negative for both groups (r=-0.21 for phytoplankton, r=-0.22 for zooplankton, p<0.001), as expected by our hypothesis for plankton. Large free-floating primary producers are indeed extremely scarce in the ocean. The advection in the open ocean can easily isolate the individuals and propagules of a macroalgae species, making the population inviable due to longer generation time. Notably, the only macroalgae species with their entire lifecycle in the pelagic zone are the two species of Sargassum (S. natans and S. fluitans), that dwell in the Sargasso Sea, situated in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre where currents might facilitate the population cohesion of these macroalgae.

If a species can move to circumvent the water viscosity and to face the current advection (i.e., nekton), then, it might actively maintain the population cohesion. Thus, species´ geographic ranges might change according to their body size and dispersal mode (passive, active). For active dispersers, the negative relation is hence suggested to be lost or even reversed. We also tested this hypothesis by relating the body length of 215 marine pelagic species with an estimate of species geographic range. The relation is weak but significantly positive (r=0.14, p<0.036), supporting our hypothesis for active dispersers.

We provide an integrative approach to explain why the marine realm is less diverse in terms of overall species richness than land, based on the primary effect of sinking and oceanic drift to body size of eukaryotic species with passive dispersal, which affects higher trophic levels:

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by the Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101059915 (BIOcean5D project). Co-Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.