The European Union (EU) is the world’s largest market for fishery and aquaculture products (FAPs). Over the last 15 years, various EU institutions have expressed concern about the increasing dependence of the EU market on imports. This is seen as a lack of competitiveness of the EU fisheries and aquaculture sector, which can only partially meet the needs of the internal market. The selfsufficiency rate is a useful indicator of the ability of the EU producers to meet internal demand.

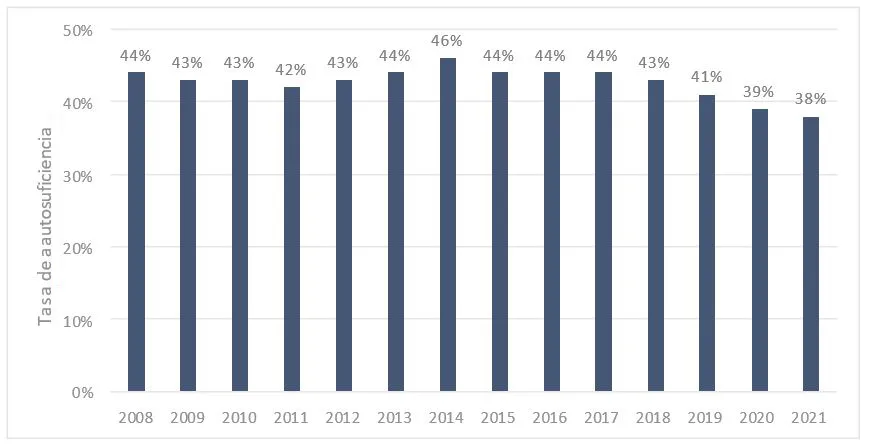

Self-sufficiency has been declining since 2008 to the point where EU producers were only able to meet 38% of demand in 2021. Some of these imports may come from countries where the conservation and management measures (CMMs) for fisheries, the hygiene and quality of FAPs, and working conditions, etc. are too lenient compared to those in force in the EU. They therefore constitute unfair competition for EU producers, who are subject to strict CMMs and control measures, and administrative procedures. It appears that the many external operators have a strong comparative advantage in terms of lower production costs, due to the less demanding legal requirements, subsidies and, in some cases, their fleets engaging in illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This study aims to identify the internal and external factors that are leading to the lack of competitiveness of the EU sector, in order to propose policy options to strengthen its competitiveness, while ensuring a level playing field between external and domestic operators.

Fisheries and aquaculture in the EU are regulated by an extensive body of legislation, covering the entire fish value chain, including not only the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), but also other legislation such as trade, food safety, labour, and environmental aspects. In turn, fishing activities must strictly comply with the CMMs through a comprehensive control and enforcement system. Increasing restrictions on the fishing fleet’s access to resources are affecting the supply of fish, while at the same time increasing operating costs. This is particularly problematic given the energy intensive nature of the EU fleet.

In turn, severe restrictions on the use of the marine space for aquaculture concessions, and the difficulties in obtaining licences limit the production of farmed fish and shellfish. Trade in EU FAPs on the internal market is also subject to the strict regulatory framework of the Common Market Organisation (CMO), which aims to ensure that products meet high standards of quality, hygiene, and labelling, among other things. As a leading player in global maritime governance, the EU must lead by example. The European Green Deal (EGD), and its 2030 Biodiversity Strategy, which aims to protect several areas identified as vulnerable marine ecosystems (VMEs), is a global reference for other countries, but may affect the competitiveness of the EU fleets vis-à-vis external operators. Emerging sectors may also limit access to traditional fishing grounds and affect offshore fish farming.

In turn, generational change in the sector, particularly in the extractive phase, harms competitiveness. There is evidence of a lack of effective customs control in some Member States, which would lead to forum shopping and thus access to the EU market for FAPs of dubious origin. Nevertheless, there are several structural elements that can strengthen the competitiveness of the sector, such as the EU research and innovation framework, which promotes more energy-efficient processes, more selective fishing, or more productive and more environmentally friendly aquaculture. For its part, the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF) offers opportunities to improve the competitiveness of the sector, provided that the funds are used more effectively by Member States and the sector, leading to more efficient processes and added value for FAPs.

Figure 1: EU’s self-sufficiency rate for fisheries and aquaculture products (FAPs) in %, 2008-2021

The EU is a world leader in ocean governance and is a signatory to several multilateral conventions and has many bilateral fisheries agreements with developed and developing countries. The EU is also party to several Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) and is active in proposing CMMs, while participating in the provision of scientific advice. The EU’s role in the international arena underpins much of the EU’s policy and legislation to protect the marine environment, and to ensure sustainable fisheries. These policies impose restrictions on the activities of the EU fleet in international and non-EU countries waters.

However, not all international actors are strongly committed to the conservation of the oceans and marine resources. Many foreign fleets and aquaculture producers are heavily subsidised, some fleets engage in significant IUU fishing activities, fishing practices affect endangered, threatened and protected (ETP) species, working conditions are poor, and product quality is not optimal. These FAPs of dubious origin are traded around the world, and there is evidence that many may find loopholes to access the attractive EU market. There is little the EU can do to promote sustainable practices by fishing fleets operating under the sovereign decisions of their governments. However, the EU can impose conditions on access to its market. The IUU Regulation and its carding system were designed with the intention of deterring the escalation of illegal FAPs’ access to the EU market. The autonomous tariff quotas (ATQs) system affects the level of tariffs to be paid, not the conditions of market access. There are currently no provisions on working conditions and alleged forced labour in non-EU countries, although these will be addressed in future legislative instruments. On the other hand, Brexit has led to a progressive loss of fishing opportunities and, consequently, economic losses for some EU fleets, increased dependence on imports and rising prices. Future negotiations on access to UK waters after 2026 will therefore be crucial.

Based on the evidence reviewed, a number of general policy recommendations are set out below, as well as a number of more specific policy recommendations based on the four case studies:

The present document is the executive summary of the study on ‘’Policy options for strengthening the competitiveness of the EU fisheries and aquaculture sector’’. The full study, which is available in English can be downloaded at: https://bit.ly/3T5f1kP

Authors: Martin Aranda, Leire Arantzamendi, Margarita Andres, Ane Iriondo, Gorka Gabiña (AZTI); Gabriela Oanta, José Manuel Sobrino-Heredia (Universidade Da Coruña); Bertrand Le Gallic (Université De Bretagne Occidentale).